Aelfgyva The Mystery Woman of the Bayeux Tapestry:

Part Four

The woman

in the Bayeux Tapestry called Aelfgyva has given commentators trouble for

centuries. As we have seen in my earlier parts, there have been plenty of

Aelfgyva’s mentioned in the 11thc but none that quite fit the bill as much as

Aelfgifu of Northampton. We have discounted

Emma/Aelfgifu and also that Earl Harold had any daughter or sister of that

name. I have also set aside the idea that she may have been a child of

William’, whom he offered to Harold as a wife in return for an alliance.

Aelfgyva was a purely English name and although it may have been a possibility,

it was not likely to have been given to a Norman woman; it was thought that

Norman’s had no liking for English names. So why then, am I going with Aelfgifu

of Northampton, King cnut’s first wife? What is it about this Aelfgifu that

draws me to believe the woman they are referring to is her?

Aelfgifu

was reported by Florence of Worcester as passing off the bastard child of a

priest as Cnut’s son after failing to provide an heir of her own. This child

was Swein. Later Worcester states that she passed off another ‘son’ Harold

Harefoot who was reputed to have been a child of a mere workman or a shoe

maker. Interestingly, if we look once again at the image of Aefgyva and the

priest, we see that in the lower border a naked figure of a man with a large

member is mimicking the stance and gesture of the priest. There is also another

image of a naked workman. The priest who

touches her face is either fondling or as some might say slapping her face. The

scene is also iconographic, which means it is supposed to be a representation

of what perhaps, William and Harold may be discussing. Unlike the other scenes

in the tapestry, this one is not to be viewed as part of the story but more as

an illusion of some sexual scandal. Interpreting the face fondling/slapping aspect is a bone

of contention, however. At first I favoured the idea that the priest was

slapping her but upon further research I came across some intriguing

suggestions that were submitted by J Bard McNulty in the Lady Aelfgyva in The

Bayeux Tapestry (1980).

Edward

Freeman (1869) suggests that the woman they are discussing was a woman at the

duke’s palace. I would disagree. As we have explored before, there could not

have possibly been a woman with this name in Normandy at this time.

Then, if

we accept that the woman referred to in the tapestry must be Aelfgifu of

Northampton, we have to ponder upon why on earth Harold and William would be

discussing her at this stage of the story. Aelfgifu would have been long dead

at the time of this meeting (around autumn of 1064). But let us not discount

her, for she was, like her counterpart and rival Emma of Normandy, a formidable

woman. Unfortunately, she was perhaps not as tactful or astute as Emma.

Aelfgifu

was Cnut’s first wife, most likely he married her in the more-danico fashion rather than officially as he was later able to marry

Emma. It was quite customary in those times for nobles to ‘handfast’ themselves

to a woman so they could at a later time marry for political reasons as Harold

Godwinson did with Aldith of Mercia. The Norman propaganda machine was to later

make much of Harold’s relationship with Edith Swanneck, referring to her as his

mistress rather than his wife, but under English law, she was just as entitled

to the same considerations as an official wife was and her children would not

have been viewed as ‘bastards’ or illegitimate and had the same entitlements as

legal offspring would have.

Cnut must

have valued Aelfgifu and her children by him, for he sent her and Swein to rule

Norway for him and as Swein was a mere child at the time, she was to act as

regent. But she was unpopular with the Norwegians, her rule being ruthless and

harsh and so she and Swein were driven out after some years and Olaf’s son Magnus

the Good replaced Swein as King of Norway. One would imagine that Cnut’s

feelings toward Aelfgifu if Northampton would have changed after she lost Norway

for him.

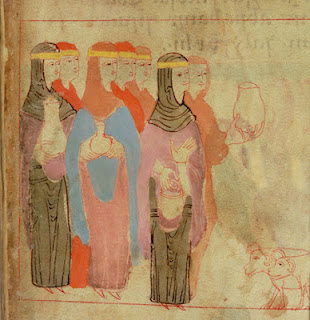

Noble women of the period

Eventually,

Magnus would make a treaty with Cnut’s son by Emma, Harthacnut that would become

the basis for Harald Hardrada’s claim to the English throne in 1066. Harthacnut

and Magnus of Norway made an oath to each other that should one of them die, the

other would inherit their kingdoms should they die without issue. Although Magnus

claimed his right to England, he never pursued it beyond a threat after Harthacnut

died. When Harald Hardrada succeeded to the kingdom after his nephew Magnus

died, he claimed that Magnus’ and Harthacnut’s oath should still stand and

egged on by Tostig, Harold Godwinson’s brother, he planned his fateful invasion

of England.

But if

the stories that had been circulating about Aelfgifu’s deception of Cnut were

to be believed as truthful by the general consensus, the two men, Harold and William,

should they be discussing all claims to the throne, would have both agreed that

Harald’s claim should be dismissed. McNulty’s suggestion is that Harold was

reassuring William that the English had discounted Hardrada’s claim, a decision

that they both agreed about and happily they both ride off to campaign in

Brittany.

Sounds

plausible? No it doesn’t. Because what had Aelfgifu’s indiscretion got to do with Hardrada’s claim

to the throne? After all, she was not mother to Harthacnut who had made the

oath with Magnus and she is definitely not the Aelfgyva depicted in the tapestry.

Just when I think I am there, another ‘but’ pops up!

In the words of the great man Sir Walter Scott, “Oh what a tangled web we weave, when first we

practise to deceive”. More in the next part of this amazing mystery.